On weirdos, wonder and the quest for meaning

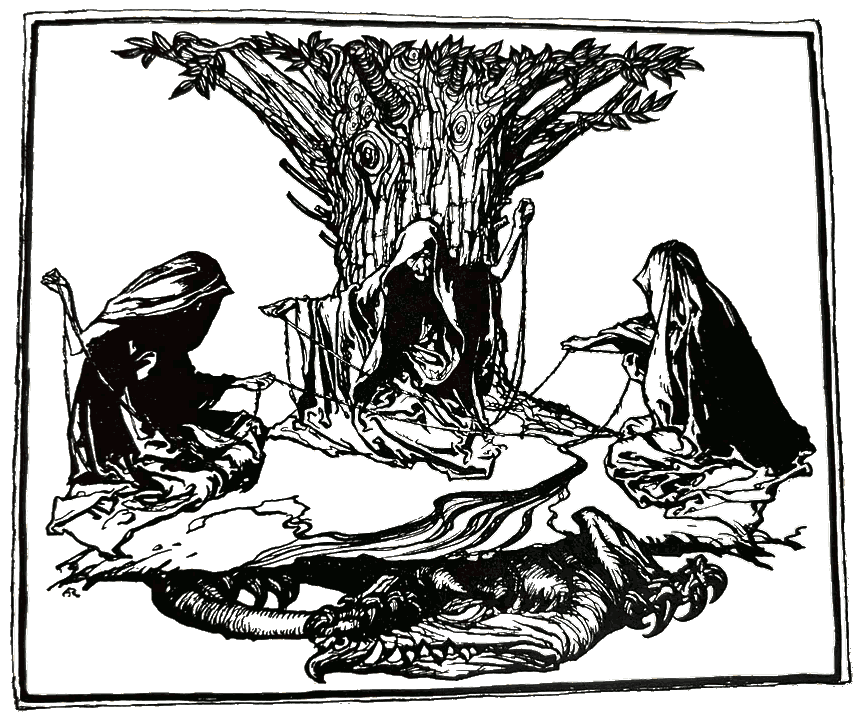

The weird and the magical have always been deeply tied up. When the term ‘weird’ first entered English, it meant ‘fate’ (or in some accounts, ‘having the power to control fate’). The three Fates from Greek mythology are also the Norns of Norse myth, who are also the Weirds, or Weird Sisters. Eventually, they became the witches in Shakespeare’s play Macbeth.

From them, we get the modern sense of ‘weird’ as something or someone out of the ordinary. A bit unsettling, a departure from the mundane. You know: like a witch… or possibly a fairy, as in Shakespeare’s main source text.

‘these women were either the weird sisters, that is (as ye would say) the goddesses of destinie, or else some nymphs or feiries, indued with knowledge of prophesie by their necromanticall science, bicause euerie thing came to passe as they had spoken’

Beyond the origin of the word, there is a long history of those perceived as odd of being suspected of magic. Some were thought to be changelings, babies swapped out for fairies when they were in the crib; others were accused of witchcraft, or demonic possession. This could lead to exclusion, and terrible punishments.

Meanwhile, some people seen as weird were revered as shamans, hermits, ‘holy fools’. The magical and the mystical attract wonder, as well as fear. The term ‘mystic’ captures a little of that; from a root meaning ‘hidden’, it suggests mysterious wisdom, and has long been associated with magical traditions, as well as a spiritual belief in direct communion with the divine.

While mystics have at times been treated with reverence, they have often been persecuted for nonconformist tendencies. Many dominant religious authorities seem threatened by the notion that individuals can connect with the divine without their help. More generally, authorities tend to have a problem with people believing in things that are supposed to be impossible.

Is that perhaps why society sometimes seems so determined to snuff out the intensity and the sense of magic that forms such a part of the fabric of childhood, as we ‘grow up’ into adulthood? Because leaving it intact would leave open too many possibilities? The connection between weirdness and the ‘power to control fate’ seems relevant here, again. To conform is to accept certain possibilities being ruled out.

In his beautiful essay ‘The squandered gift’, Karl Thomas Smith writes about the film Kiki’s Delivery Service, in which a young witch, growing up, finds her magic slipping away from her:

what comes for Kiki – and throws her world into gloomy disarray – is the weight of crushing normality. Instead of a campy, cloak-swishing villain, the “bad guy” here is life and what it does to people who are special – people who are different.

Karl Thomas Smith, Now Go: On Grief and Studio Ghibli,

Perhaps it is understandable that people feel threatened by those who don’t fit in with their view of how the world works – whose outlooks, or very existence, seem to imply that their horizons are too narrow (although to be fair to the people of Koriko, Kiki was never shunned for her differences).

In the end, we are all struggling to make sense of living brief lives in an incomprehensibly vast and seemingly erratic universe. As joyous as it can be to wonder at the mystery of it all, it is also natural to seek comfort in things that help us to feel like we have at least some idea what’s going on.

Tiger got to hunt, bird got to fly;

Kurt Vonnegut (as Bokonon), Cat’s Cradle

Man got to sit and wonder ‘why, why, why?’

Tiger got to sleep, bird got to land;

Man got to tell himself he understand.

It looks as if the same desperate drive to make sense of things might help to explain both the human tendency towards magical thinking, and the problems people seem to have with nonconformity – with people, and things, that resist categorisation.

Writing here about weird fiction, Mark Fisher could just as easily be describing weird people:

As we shall see, the weird is that which does not belong. The weird brings to the familiar something which ordinarily lies beyond it

Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie

Tales of the uncanny, and people who stand out as not fitting in, have a way of ‘weirding‘ the world – causing a shift in perspective, reminding people that their understanding of things is limited, that some of their assumptions might be deeply wrong. This can obviously be unsettling, but it can also feed a sense of curiosity and wonder. As the problematic pioneer of weird fiction, H.P. Lovecraft put it, he was working to visualise

the vague, elusive, fragmentary impressions of wonder, beauty, and adventurous expectancy which are conveyed to me by certain sights[…], ideas, occurrences, and images

H.P. Lovecraft, Notes on Writing Weird Fiction

The urge to share those sorts of impressions, and the challenge of doing so, will be familiar to many of those seen as weird. It may be one of the reasons we are seen as weird – for better and worse. Seeing things differently is both a blessing and a curse for many artists, writers, scientists, neurominorities and sundry weirdos.

Helping people to see wonder in the world around them is arguably one of the central roles of art, but folk can be brutal about enthusiasms they don’t share. Not much screams does not belong like someone visibly having intense feelings about things that are of no interest to those around them.

The world works hard to beat out of us the things about which we care the most – to dilute our passions and temper our reactions. The world at large, to its great shame, is scornful of people who live deeply.

Karl Thomas Smith, Now Go: On Grief and Studio Ghibli

Even when they value the sparkliness of new perspectives and unfamiliar joys, people may not want to know about the difficulties that come with them. It is not hard to see why the ‘manic pixie dream girl‘ is such a familiar trope – serving as a hyperactive reminder of the importance of really living – of seizing the moment, and following your dreams, and all that. That is not necessarily a fun or healthy thing to be though, as Laurie Penny described in 2013:

I refuse to burn my energy adding extra magic and sparkle to other people’s lives to get them to love me. I’m busy casting spells for myself. Everyone who was ever told a fairytale knows what happens to women who do their own magic.

Laurie Penny, I was a Manic Pixie Dream Girl

It is perhaps significant that some time later, they realised they’re autistic.

Wherever we draw it from, viewing the world with a sense of enchantment is a deeply powerful thing. Logical reasoning is an essential tool for making sense of this chaotic world, but it can’t always provide satisfactory answers to the most centrally important questions. Who are we? Who and what should we care about, and how much? Why should we even bother getting out of bed?

Answering these vital questions usually depends on stories, and feelings of connection. Logic might help us to hammer out some of the details, but it is risky to use it to undermine the answers that other people have found.

Just as everything seems so desolate, when we feel so isolated and afraid, confused and exhausted, when anger threatens to taint our entire social order, many of us are yearning for something that connects us again, that draws us back into our bodies, and tethers us to our landscapes.

Katherine May, Why Magic matters

Kurt Vonnegut wrote in Cat’s Cradle about the importance of ‘harmless untruths’ to a lot of people, what he called ‘foma’:

Live by the foma that make you brave and kind and healthy and happy.

Kurt Vonnegut (as Bokonon), Cat’s Cradle

Of course, it is not always easy to know which untruths are actually harmless – or which beliefs will bring out the best in someone, whether or not they are objectively true. The rationalist tradition focuses heavily on truth, and there is value in that, but humans don’t only work on truths. Even when people believe things that make them a danger to themselves or others, stories and connection may do more to bring them round than straight facts. Recognising shared humanity goes a long way.

Some people may need myths, and rituals, and space for their own feelings, to live a life that makes sense to them. That doesn’t have to mean believing anything untrue – at least, not for everyone. Facts are largely just beside the point when it comes to these things. Activist and writer adrienne maree brown has this advice “for anyone having a hard time believing in magic, who also knows it is important to do so”:

the core practice, in my limited but dazzling experience, is to notice anything that makes you feel like wow. it can be parts of the universe, the moon, a family member, a lover, a beloved, a commitment, a skyline, a fact, a feeling, a fiction, a seemingly insignificant part of the world under a microscope

adrienne maree brown, believing in magic

Perhaps everyone needs a little bit of wonder in their life: a spark of something along the lines of magic to get them through. Perhaps some need a lot more than others, though, and we certainly find it in very different places.

That seems to be part of the reason so many of us find each other so weird. The history of religious and cultural friction shows how dangerous that can be, but perhaps we could do better if we learn to embrace the weirdness. Surely there is a kind of magic in the mystifyingly diverse ways that people find meaning in their lives?